A Global Tour Through Russian Propaganda

Where Russian narratives on Ukraine are winning, where they're losing, and where they're not even competing.

The idea that Ukraine is winning the information war against Russia is axiomatic if one focuses on Western headlines. Ukraine has quickly debunked false Russian claims of Ukrainian “Nazis” around every corner, while Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky’s video updates from the streets of Kyiv led global news broadcasts. Ukraine’s successes have been buttressed by social media companies working to proactively label and limit Russian overt state-owned media, curbing the reach of Moscow’s propaganda machine.

But the narrative battle extends far beyond the English language. Russia’s propagandists recognize this, and through curated messaging and narrative spread via local media outlets they’ve successfully muddied the information waters from Latin America to the Arab world to Southeast Asia.

Attempting to measure Russia’s reach in various languages will always be an imperfect science. While empirical metrics, such as share counts, can be indicators of influence, their effectiveness is limited when both overt and covert media are considered. As such, Russia’s influence through its propaganda in various languages might better be estimated by considering multiple indicators—both quantitative and qualitative. The metrics used in this article to approximate the impact of Russian online propaganda around the world at the time of this writing include:

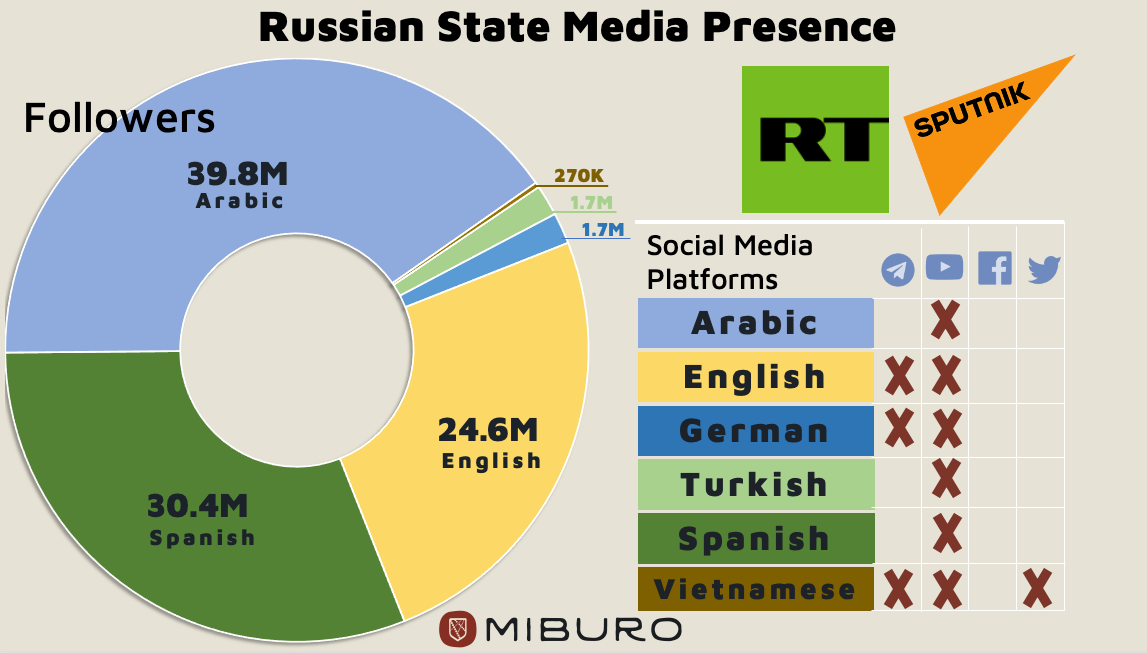

1) Russian overt media’s access to social media platforms (number of operational RT and Sputnik accounts remaining);

2) The number of followers of these social media pages; and

3) The ability of Russian talking points to reach and spread in regional print and digital media.

The last metric relies on pro-Russian propaganda’s ability to penetrate local coverage. These are articles, social media posts, and videos that further an idea or claim promoted by the Kremlin—such as the idea that NATO expansion caused the war in Ukraine—without any observable link between the content itself and Russia or its propagandists.

Pro-Russia Mad Libs

Any one of us can play this propaganda game of Mad Libs that so often emerges after Russian government talking points proliferate and morph online. Think of a region in the world and fill in the usual bogeymans and scare tactics into the general headline. Here’s the prompt:

The headlines below reflect actual headlines and narratives pushed to each audience in both Russian state-owned media (like RT or TASS) and non-Russia-backed media sources echoing Russia’s typical talking points.

The messages can also be filtered to narrower audiences within a language. Such is the case in English:

How common in localized coverage these narratives seem to be is how we estimated Russia’s success on the third metric (Regional Media Infiltration) in the graphic below:

Where Russia is Winning

Russia is doing well in languages where it has invested large amounts of resources for years. Russian state media has some of its largest followings on its Arabic and Spanish-language social media pages with at least 30 million combined followers each on RT and Sputnik. After Russian, RT publishes its highest volume of articles in Arabic and Spanish.

Even as YouTube has imposed stricter moderation on official RT and Sputnik channels, young Russian influencers who previously starred in RT’s videos have personal YouTube channels, which continue to reach subscribers. Nastya Svib, a Russian RT Online contributor, has over 585k followers on her YouTube channel where she continues to post her workouts, comment on Arab politics, and collaborate with Arab vloggers.

Russian propaganda also finds a home in native Arabic-language media. Pro-Russia Bulgarian “journalist” Dilyana Gaytandzhieva, who has promoted conspiracies about biolabs in line with Kremlin talking points, had some of her original reporting aired by Lebanon-based outlet al-Mayadeen. Since the start of the Russian invasion, the U.S.-sanctioned Russian ideologue Aleksandr Dugin has been featured on Qatari-owned al-Jazeera’s programs, in addition to reportedly Iran-backed Iraqi Telegram channels, and al-Mayadeen, where he has argued that Russia is protecting the world from an unaccountable U.S.

According to NBC reporting, RT Spanish is the third-most shared site on Twitter for Spanish-language information on the Russian invasion. User interactions with RT Spanish’s Facebook page reportedly tripled after the invasion of Ukraine. Russia often targets progressives and left-leaning audiences in Latin America. During the Russian invasion of Ukraine, Russian messaging targeting Spanish speakers has employed these leftist themes, claiming the conflict is a continuation of U.S. covert action supporting right-wing governments around the world. Multiple Latin American state media outlets also reliably repeat Russian propaganda. For example, Pan-Latin American news station teleSur—which is sponsored primarily by the government of Venezuela—consistently runs official Russian state media lines including the accusation that Ukraine is preparing to attack Orthodox churches.

Where Russia’s Narratives are Winning

There are places where Russia has invested little in state media, but its message resonates with local audiences. Turkish and Vietnamese-language content exists in Sputnik but not in RT, and the follower counts of both languages on respective social media pages is low. Nonetheless, pro-Russia messaging has been reaching these audiences.

In Turkey, Sputnik was able to build a following by writing about events that most mainstream Turkish newspapers would censor, like critically covering a prosecutor demanding life sentences for Turkish protests. Outside of Sputnik’s limited reach, the Aydınlık newspaper and Ulusal TV channel—with over 1.5 million combined followers on their social media pages—regularly feature content from Russian, U.S.-sanctioned outlets, like Yevgeny Prigozhin-linked United World International, and feature guests like the chief editor of U.S.-sanctioned Russian news outlet Geopolitica. The outlets regularly call for Turkey to leave NATO and describe the U.S. as a global aggressor. The anti-Ukraine content in Turkish is curated for a Turkish audience, with claims that Zelensky is a sympathizer of Fethullah Gülen—Turkey’s most-wanted man accused of of plotting the failed 2016 coup—and that foreign fighters coming to fight for Ukraine previously fought with anti-Turkey Kurdish forces in Syria. These messages seem to be tipping the scale in Russia’s favor. In a March 2022 poll conducted by Turkish polling agency Metropoll, 48% of Turks blamed the U.S. and NATO for the situation in Ukraine while only 33.7% blamed Russia.

In Vietnamese, a network of at least a dozen Facebook pages and groups has been found to be promoting pro-Russia narratives about Ukraine to an audience of over one million followers, though it is unclear whether these pages are authentic or not. These pages share content from a set of recently created and seemingly inauthentic Vietnamese Facebook profiles. Some of these Facebook pages are run by page managers in Russia. Vietnamese Facebook networks sharing pro-Russian narratives appear to have an unusual focus on the superiority of Russian military equipment, not typically seen in other language’s pro-Russian content. Russia is likely using the war in Ukraine in an effort to advertise its military industrial complex to Vietnam, which is Russia’s fifth largest arms customer.

Where Russia is Not Competing

Russia is doing poorly where it has no overt media reach. RT and Sputnik produce no overt content in Hebrew or Hindi, but Russia-aligned narratives do manage to reach those languages' audiences in limited ways. Pro-Russian narratives are not mainstream in the Hebrew media environment, but do pop up from Israeli social media personalities. There are efforts by independent journalists and prominent social media users in Israel to link Ukraine to Nazism. However, these social media posts are not very popular—rarely receiving more than a few thousand likes—nor seemingly coordinated. Alternatively, in Hindi, Russia may have attempted to spread pro-Putin messages through coordinated inauthentic behavior as described by Carl Miller, a researcher at the Centre for Analysis of Social Media. Twitter banned more than 100 such accounts which had used the hashtag #IStandWithPutin in 2022. Despite these efforts, blatant Russian propaganda is not mainstream in India, as Indian journalists call for the formation of a neutral “Indian narrative” on Ukraine.

Where Russia Has Been Deplatformed

There are also spaces where Russia has done poorly despite investments due to restrictions on its media. RT and Sputnik have lost about a third of their audiences in German. Telegram, TikTok, and Facebook all announced they would restrict access to RT and Sputnik in the EU, while Germany took RT German off the air in December 2021. Despite this, in limited ways, Russian propaganda narratives have been able to penetrate German social media pages through individual influencers with relatively low followings like Alina Lipp or through the sharing of RT articles on pro-Russian Facebook pages. However, there are also robust German efforts to debunk these narratives, with websites like correctiv.org calling out false claims.

There are languages where despite restrictions on Russian state media, Russian narratives are able to persist. Russia has struggled to access many English-language social media platforms after its invasion of Ukraine. RT America ceased production after many U.S. satellite carriers dropped the network. And while RT’s English video content found a new home at Rumble after being removed from YouTube, engagement on Rumble is poor, with many videos unable to receive even 1,000 views days after being posted.

Despite the loss of nearly a dozen of its channels, Russian state media has maintained lines of communication to the English-speaking world. Russian messaging has been so persistent that it can still rely on the organic sharing of Russian disinformation and propaganda. Russian narratives have made it onto podcasts with millions of subscribers and reportedly Russian intelligence-linked websites like Veterans Today. What has changed since 2014 is that English-language media outlets will quickly debunk Russian propaganda and disinformation drives, clearly labeling the claims as falsehoods, rather than ignoring them or debating them as equal opinions alongside truth.

The Russian messages that have seeped into the English-language information space evolve to play to U.S. audiences, such as linking Hunter Biden with the development of the nonexistent American biological weapon facilities. RT and Sputnik social media pages posted coverage that mentioned the phrase “biological laboratory” in English at least three times as much as any other language from 24 February to 29 March.

Conclusion

Russia has faced significant blows to its global influence operations in recent years due to proactive efforts by Ukraine, western governments, and social media platforms. But merely removing its official channels from social media platforms will not be enough to prevent its misinformation from reaching global audiences. Russia has spent years investing in messaging to global audiences, and the messages Russia-aligned actors spread have in many cases permeated to local media outlets. If the West wants to combat Russia in the global information war, more attention can be paid to proactively countering Kremlin messaging in local media in non-English languages.