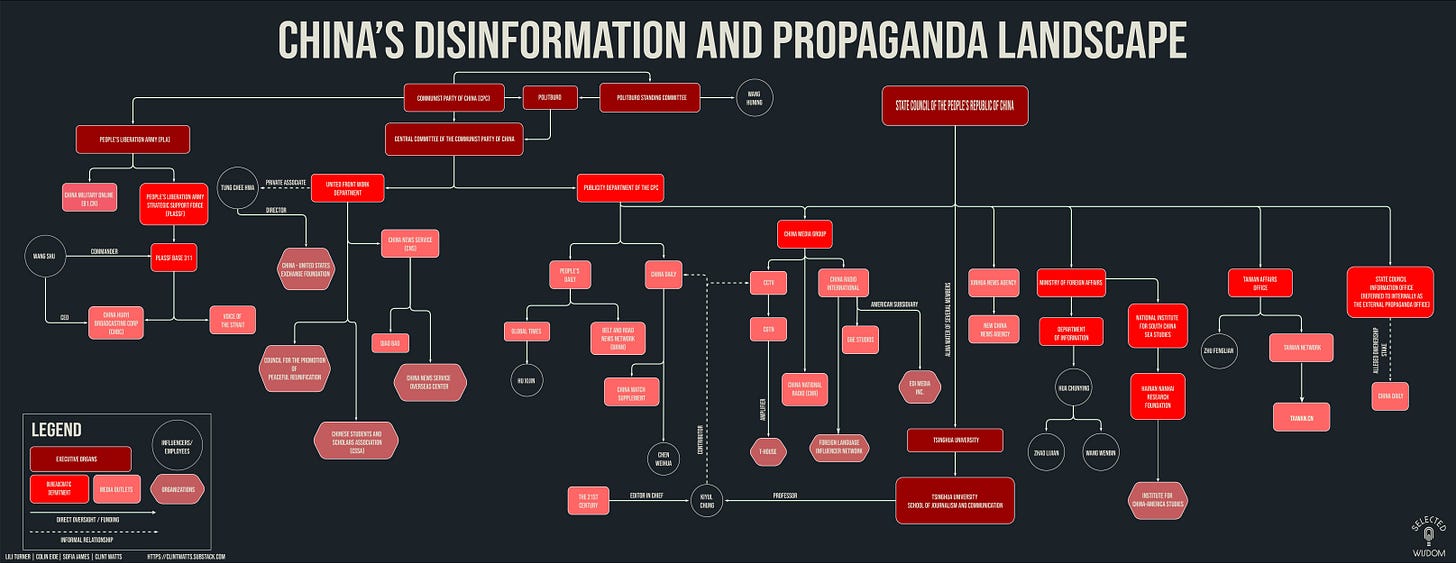

China's Propaganda and Disinformation Landscape - 2021 Snapshot

China's Top-Down Approach to Messaging: A Subtle Force We Should Not Ignore

The Chinese Communist Party (CCP) is not copying Russia’s playbook when it comes to propaganda and disinformation—they’re authoring their own, and it comes with loads of cash and lots of tech that Russia can only dream of having. While Iran is building local partner capacity to push the Islamic Republic’s line to predominantly regional audiences and Russia pursues political warfare active measures campaigns abroad, China has grown its audience share globally, maintaining centralization and control, through a different multi-pronged approach combining well-funded, overt state-run print, radio, and television media; a network of public-private partnerships; and a new generation of social media influencers softening the CCP’s image worldwide.

The Producers – China’s Sprawling State Media Behemoth

By and large, all Chinese state media (CSM) content is formulated from the top and trickles down through individual outlets. Higher-ups within executive organs including the Publicity Department of the CCP (中国共产党中央委员会宣传部) decide the direction in which media consumers should be influenced and what stories should be placed front and center for audiences. Then, outlets create content that works towards this purpose—CSM itself has described this as the “central kitchen” (中央厨房) model of distribution.

Content across CSM outlets and social media platforms is uniform in its stance on key issues, and messages rarely contradict one another. However, messaging might differ slightly depending on the target audience. Each of the following executive organs has a distinct purpose coupled with a distinct set of audiences.

China Media Group (CMG) is a powerful media conglomerate operating in the PRC. It is directly overseen by the Publicity Department of the CCP, which also oversees the popular outlets People’s Daily and China Daily. However, CMG is functionally separate from these two entities and is responsible for overseeing China Radio International (CRI) and China Central Television Network (CCTV), including CCTV’s wide-reaching, internationally focused subsidiary China Global Television Network (CGTN). These outlets all have a specific focus on repackaging and disseminating CSM content in a variety of languages to reach audiences abroad, and form a key part of the CCP’s Grand Overseas Propaganda Campaign (大外宣), its mission in “telling China’s story well”. CRI in particular broadcasts in at least 60 languages and has been found to direct a vast network of Chinese nationals that speak a variety of foreign languages operating as “influencers” on social media, who obscure their ties to CSM. (See “‘The One Like One Share Initiative’ - How China deploys social media influencers to spread its message” for more information on the CRI influencer initiative, a network that was able to attract nearly 19 million followers on Facebook alone, a total that has expanded since the publication of our initial post.) CCTV produces content in Chinese in addition to other languages, whereas CRI and CGTN do not produce Chinese content and focus solely on foreign-language content targeting international audiences.

Above: Hindi-language CRI influencer Meera on a trip to Tibet, reporting that Tibetan people are happy and have been lifted out of poverty. Tibet may be of particular concern to Hindi- and Nepali-language audiences due to the proximities of Tibet, India, and Nepal.

(Source: Meera चीन की मीरा)

Below: A clip of a CGTN special entitled "What's China's 're-education camp' in Xinjiang really about?" CGTN's Xinjiang-related content is particularly up-front in its denial of Uyghur oppression. (Source: CGTN)

The United Front Work Department (UFWD) is directly overseen by the Central Committee of the Communist Party of China (CCCPC), which is the CCP’s organ of highest authority. Like CMG, the UFWD targets audiences abroad. The stark difference between the two is that the UFWD has a special focus on ensuring that elite, powerful members of the Chinese diaspora remain loyal to the CCP. The UFWD seeks to influence those diaspora Chinese with economic, social, or political influence. For example, the UFWD has contributed to Chinese influence over politics in Australia and New Zealand, at least in part by way of businessmen with ties to the CCP. Diaspora communities in the U.S. and Canada are similarly firmly in the crosshairs of the UFWD’s influence operations.

The UFWD not only seeks to influence established adults, but also young people. One prominent subdivision of the UFWD is the Chinese Students and Scholars Association (CSSA). Chapters of the CSSA can be found at universities around the world, including several in the United States. While CSSAs portray themselves as student-led organizations providing a sense of community for members of the Chinese diaspora abroad, there is evidence that they receive funding from the Chinese government (by way of local consulates) for events and activities. CSSAs often release statements that criticize events at their home universities that they perceive as threatening China or the Chinese government. The UFWD has also set up sham think tanks, like the China Cross-Strait Academy, to influence Taiwanese youth’s perceptions of cross-Strait relations.

The Chinese military is also responsible for some of the most successful influence techniques and operations used by the Chinese government. The People’s Liberation Army Strategic Support Force (PLASSF) is an agglomeration of the PLA’s psychological and information operations capabilities. Base 311, a subset of the PLASSF, is tasked with conducting influence operations and psychological operations, often against the island of Taiwan. It runs at least two media outlets (Voice of the Strait and China Huayi Broadcasting Corporation) that encourage Taiwanese citizens to view the Taiwanese government with skepticism and distrust. Wang Shu (汪澍), the Commander of Base 311, holds leadership positions at both media outlets. The Taiwanese government has accused Base 311 of directing extensive disinformation operations on Facebook ahead of the 2016 and 2018 Taiwanese election cycles.

The Private-Sector Partnerships – Extending China’s Reach

In addition to overt and CSM-affiliated propaganda, China continues to grow as a covert actor in the computational propaganda space. In both 2019 and 2020, China was caught carrying out information operation (IO) campaigns on Twitter and Facebook. There’s more to the story than IO campaigns that have been attributed directly to the CCP, however. Spamouflage, a suspected private-sector actor that has not as of yet been directly attributed to the CCP, aligns its message, content, and timing with CSM, often copy-pasting verbatim quotes from CSM and official government statements into its posts. So far, this actor has been caught spreading CCP-aligned disinformation four times on Facebook, Twitter, and YouTube, and shows no signs of slowing down.

Apart from Spamouflage, companies like Onesight (一网互通), Nothing Technologies (无为科技), Urun Big Data Services (云润大数据服务), Chinaii (中国网络情报中心), and others have also assisted in the government’s censorship and propaganda campaigns. Simply put, the CCP wants to have it both ways. While happily amplifying its own propaganda abroad with bots and sockpuppets, the Party makes use of the private sector at home to clamp down on the information environment, issuing official directives to “resolutely control anything that seriously damages party and government credibility and attacks the political system”. According to one former Weibo employee, this includes fostering an ambiance of competition among social media companies, where each competes in hopes of building the optimal censorship tool.

The Influencers

In 2020, the CCP took to social media with ferocity, increasing the scale of both their overt and covert propaganda campaigns on international social media platforms such as Facebook and Twitter. While overt Chinese government and CSM accounts often are labeled as such on Facebook and Twitter, social media platforms are also inconsistent in applying labels disclosing these ties, often failing to label CSM-affiliated content in different languages or when influencers are not ethnically Han Chinese. As previously reported, we have discovered an extensive network of CRI influencers fluent in foreign languages that do not overtly disclose their links to CSM. These influencers create feel-good lifestyle content that glorifies Chinese culture, Chinese innovation, and the Chinese language, echoing the tone of “cheerleading” propaganda seen from paid Chinese government trolls in past years. Influencers also celebrate the relationship between China and the target country or region where the influencer is based, assuring their audiences that a relationship with China is mutually beneficial. Influencers speak foreign languages at near-native proficiency and many claim to have attended Beijing Foreign Studies University. These languages range from widely spoken ones like Arabic, Spanish, and Hindi, to less commonly spoken languages such as Hausa, Sinhala, and even Esperanto. However, CRI does not have a monopoly on influencers. Many journalists associated with CGTN and Xinhua have influencer-like presences on social media, although their content is more political and can be more controversial, and these journalists at times disclose their employment by CSM.

There is a smaller subset of influencers that likely do not have ties to CSM, and if they do, they are entirely obscured. These influencers are foreign CCP sympathizers (mostly Europeans and Americans) that create social media content that mirrors CSM-affiliated influencer content and echoes, or directly repeats, CSM talking points. Many of these influencers have even appeared on CSM outlets as “foreign bloggers” or “travelers” in attempts by CSM to illustrate that some foreigners have an affinity for China. Foreign influencers promote China and Chinese culture to international audiences, create feel-good travel and lifestyle content, and sometimes attempt to debunk widespread criticisms of China (e.g. mass detainment of Uyghur Muslims in Xinjiang). As reported in one BBC article, one of these influencers defends his content by claiming he has “never been paid to go on a trip” by the Chinese government. While this may be true, it also conveniently elides the monetary incentives that the modern digital economy can offer to those who megaphone the CCP’s message on their social media channels. Being featured in CSM outlets translates to more followers and clicks for these influencers, which means increased revenue from posting videos, even when direct payments aren’t received.

Why we should worry about China’s multi-media expansion

As we noted at this Substack a few months ago, people tend to believe that which they see first and that which they see the most. China’s influence operations grow every day and with each media outlet acquisition and influencer deployment the CCP increases its ability for its messages to be the first thing people around the globe read, see, or hear and that which the entire world sees the most. China’s messages often don’t resonate in the mainstream, but the number and frequency of broadcasts and posts in aggregate, over a sustained period of time, won’t just get the CCP’s message out to the world but will reshape societal perceptions about the truth and reality. Democracy’s voice is at risk of being drowned out by China’s media juggernaut, and the West has no time to wait in assessing and countering the CCP’s propaganda and disinformation onslaught.